The most profound rules of software development.

Category 1: On System Evolution & Complexity

These laws describe the inherent nature of how software systems behave over time. They are not rules to follow but truths to accept and manage.

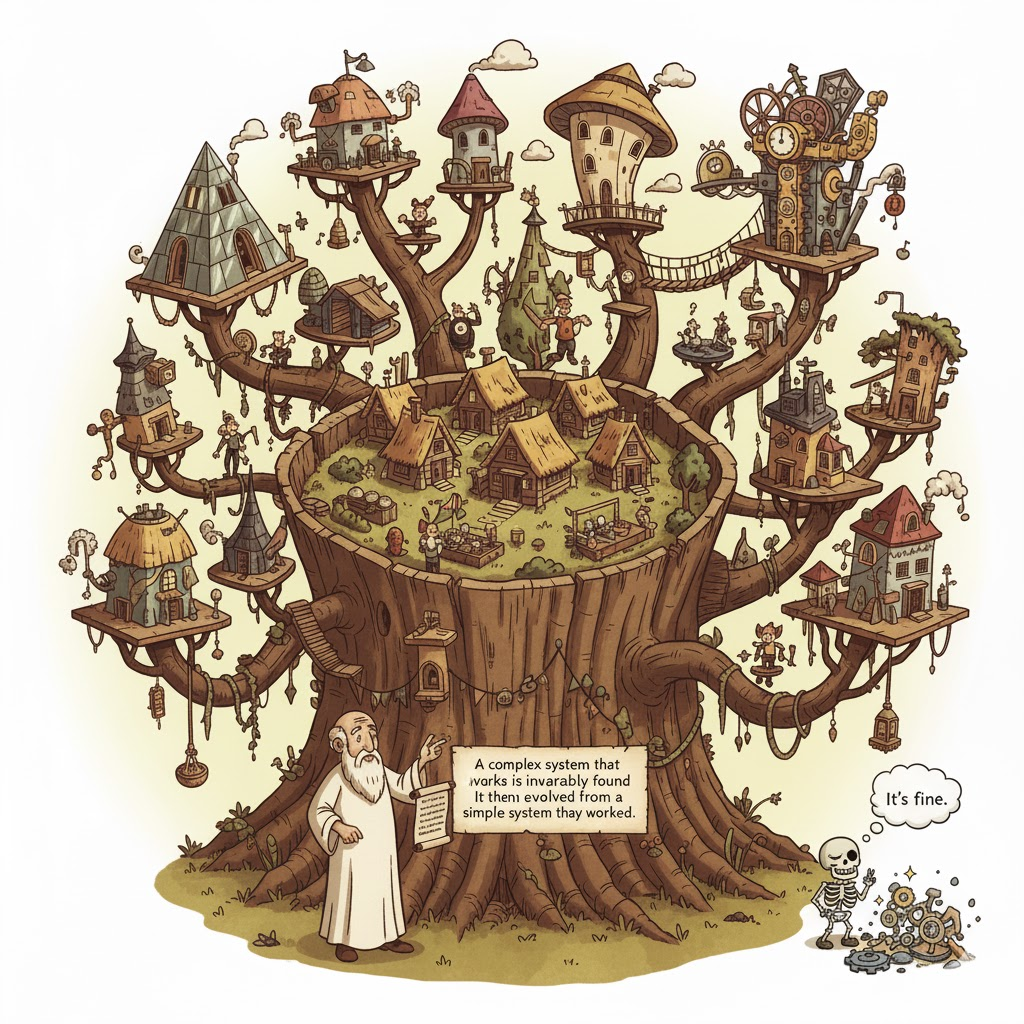

1. Gall's Law: A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked.

- Profound Truth: Functional complexity cannot be successfully designed all at once. True, robust complexity can only be achieved through an evolutionary process, as a simple, working system provides essential feedback that is impossible to predict in a purely theoretical design.

- Implication: Start with a minimal viable core (an MVP) and iteratively add functionality. This ensures the system remains stable and functional at each evolutionary step.

- Failure Example: Denver International Airport Baggage System. Instead of evolving from a simpler system, an incredibly ambitious, fully automated baggage handling system was designed from scratch in 1995. The overwhelming complexity of the "big bang" design meant it never worked reliably, leading to massive delays in the airport's opening, costing over $500 million, and ultimately being abandoned.

- Mitigation Example: The World Wide Web. The Web began with three elementary, working components from Tim Berners-Lee: HTML, HTTP, and URLs. This minimalist, functional system provided immediate value. It was then able to evolve incrementally over decades, adding CSS, JavaScript, and the vast ecosystem of complex applications we have today, demonstrating a perfect adherence to the rule.

- A Story from the Trenches: I once worked at a big corp that spent two years and millions of dollars on a "next-generation platform" designed by architects in an ivory tower. It collapsed under its own weight before a single customer saw it. A few years later, at a startup, four of us built a scrappy, ugly, but working prototype in three months. That prototype got funding, evolved, and is now a system handling millions of requests. The lesson is seared into my brain: all the beautiful diagrams in the world are worth less than a straightforward system that actually works.

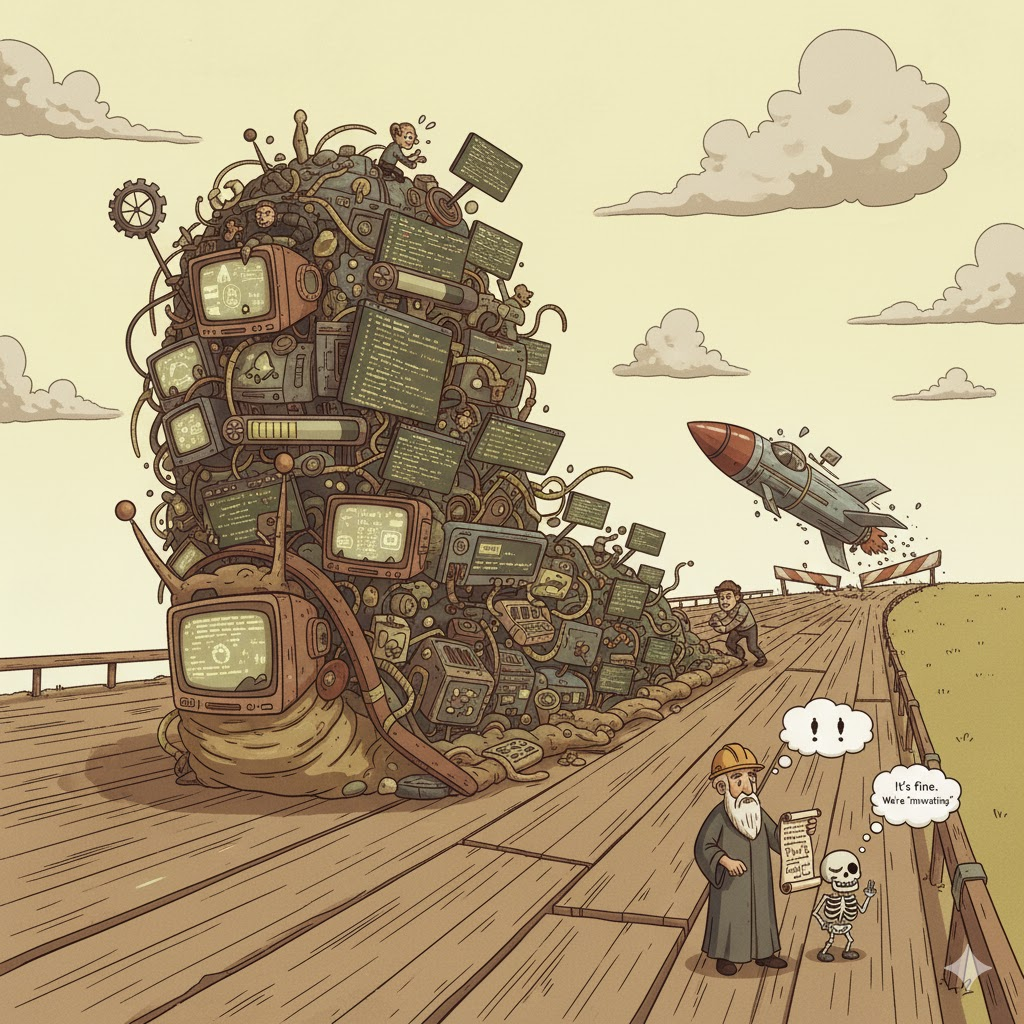

2. Lehman's Laws of Software Evolution: A system must continually change, and its complexity will increase unless actively managed.

- Profound Truth: Software is not a static artifact but a living entity that degrades over time without active maintenance. This evolution introduces complexity and technical debt, making future changes harder until the system ossifies.

- Implication: A significant portion of software cost is in long-term maintenance. A budget for refactoring and managing complexity is not a luxury; it is a necessity for the system's survival.

- Failure Example: The Netscape Navigator Codebase. By version 4, the browser's code had become a "big ball of mud." Years of adding features without actively managing the resulting complexity made the codebase nearly impossible to improve. This inability to evolve led to the decision to scrap it and start over, a delay that allowed Internet Explorer to capture the market.

- Mitigation Example: Google's "Code Health" Culture. Google actively manages its massive monorepo by treating code maintenance as a first-class engineering activity. They have dedicated tools for large-scale refactoring, a clear process for deprecating and deleting old code, and a culture where improving the health of existing code is a valued and rewarded contribution.

- A Story from the Trenches: My first "senior" role was being assigned to a five-year-old "cash cow" product. No one had touched the core in years. The original developers were long gone. Every bug fix was like navigating a minefield. We called it "archaeology-driven development." It taught me that technical debt is a loan you can manage, but if you never make payments, it turns into technical rot. And rot is unsalvageable.

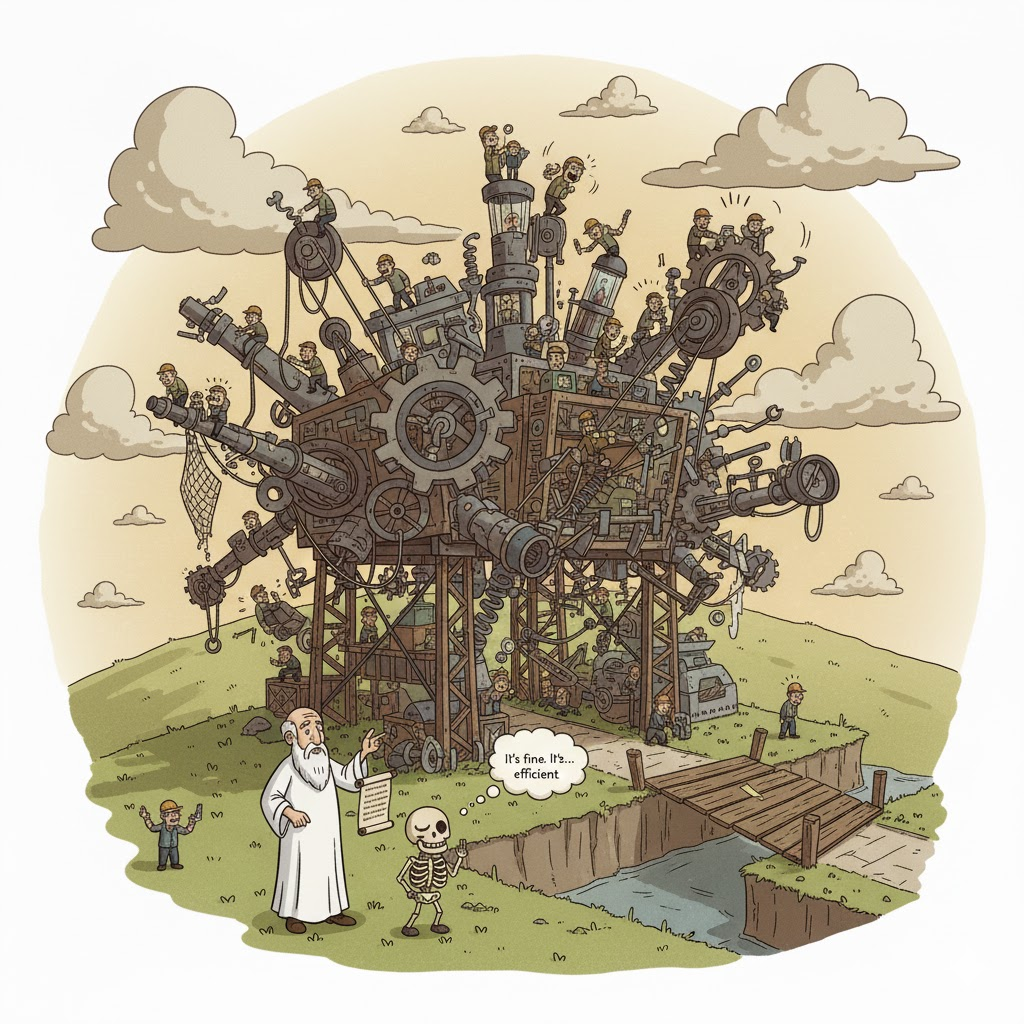

3. Brooks's Law: Adding human resources to a late software project makes it later.

- Profound Truth: The primary challenge of software is managing its invisible, non-linear essential complexity. Unlike a physical task, this complexity is not easily divisible. Adding more people exponentially increases communication overhead, making management harder, not easier.

- Implication: The main challenge is not writing code, but conceiving and managing the abstract structures of the solution. Small, focused teams are often more effective than large ones.

- Failure Example: The IBM OS/360 Project. This is the definitive case study where Fred Brooks himself learned this lesson the hard way. The massive operating system project was falling behind schedule. The conventional management response was to add more programmers. Still, the time spent training them and the exponential increase in communication overhead caused the project to fall even further behind schedule.

- Mitigation Example: Amazon's "Two-Pizza Teams." Amazon famously structured its organization around the principle that any team should be small enough to be fed by two pizzas. This intentionally minimizes communication overhead, increases ownership and autonomy, and allows teams to move much faster, directly mitigating the risks described by Brooks's Law.

- A Story from the Trenches: I lived this. We were six months late on a distributed transaction coordinator. Management "helped" by assigning a "SWAT team" of eight more engineers. My calendar instantly filled with onboarding sessions and design meetings. My coding time went to zero. We shipped six months later than the revised deadline. I learned then that on a late project, the most valuable resource isn't more people; it's uninterrupted time for the people who are already there.

4. Wirth's Law: Software is getting slower more rapidly than hardware becomes faster.

- Profound Truth: As hardware capabilities increase, the economic pressure to write efficient code decreases. This leads developers and businesses to add more layers of abstraction and features, which collectively consume the hardware gains.

- Implication: Performance and efficiency are not problems that hardware will solve on its own. They require conscious effort through optimization and disciplined feature development to prevent software bloat.

- Failure Example: Windows Vista. Upon its release in 2007, Vista was notoriously slow, bloated, and resource-hungry. Its hardware requirements far outstripped what typical computers had at the time. The resulting poor performance led to widespread user frustration and many businesses "downgrading" back to the much leaner Windows XP.

- Mitigation Example: The Video Game Industry. High-end game developers (like id Software with DOOM) operate with a deep understanding of this law. They create highly optimized game engines designed to extract every ounce of performance from fixed console hardware, demonstrating a culture of extreme efficiency that stands in stark contrast to the bloat of many desktop applications.

- A Story from the Trenches: Early in my career, I wrote firmware for a controller with 16 kilobytes of RAM. Every single byte mattered. We spent days optimizing to save a few hundred bytes. Last year, I saw a cloud service that used a 2 GB container to poll an API and write a value to a database. The discipline learned from scarcity is priceless. Modern hardware has made us incredibly productive, but it has also made many of us lazy.

Category 2: On Design & Architecture

These principles guide the high-level structure of a system. They are about how to decompose a problem and organize the solution before the code is even written.

5. Parnas's Law (Information Hiding): Decompose systems into modules that hide design decisions likely to change.

- Profound Truth: This is deeper than just encapsulation. The goal of modularity is to build walls around uncertainty. Each module should hide a "secret"—a design decision you are not sure about—allowing the rest of the system to remain stable even if that decision changes completely.

- Implication: Good architecture is about preparing for change by isolating the "hard parts" and "unstable parts." It is a direct reflection of the system's anticipated evolution.

- Failure Example: The Knight Capital Trading Disaster (2012). A new deployment accidentally activated old, disabled code. Because the old code's implementation was not properly hidden or isolated, it disastrously interpreted a new instruction, costing the company $440 million in 45 minutes and leading to its collapse.

- Mitigation Example: Docker Containers. The Docker platform is a masterclass in information hiding. A Docker container provides a standardized interface that hides the "secret" of the underlying operating system, dependencies, and hardware. This allows an application to run predictably everywhere.

- A Story from the Trenches: I was on a team building a new event-driven system. The architect insisted we use a brand-new, unproven message queue because it promised incredible performance. A wise, older engineer on the team argued, and when he lost, he did the next best thing. He created a simple internal wrapper with two functions:

publish(event)andsubscribe(topic). He forced everyone to use this wrapper and forbade anyone from using the native client library with all its fancy, specific features. We all grumbled about it. A year later, the message queue company was acquired and their product was shut down. We had to migrate to a standard cloud queue. Because of that wrapper, the change took one engineer two weeks. Without it, we would have spent six months untangling the old library from dozens of services. That engineer didn't just write code; he built a firewall against the future.

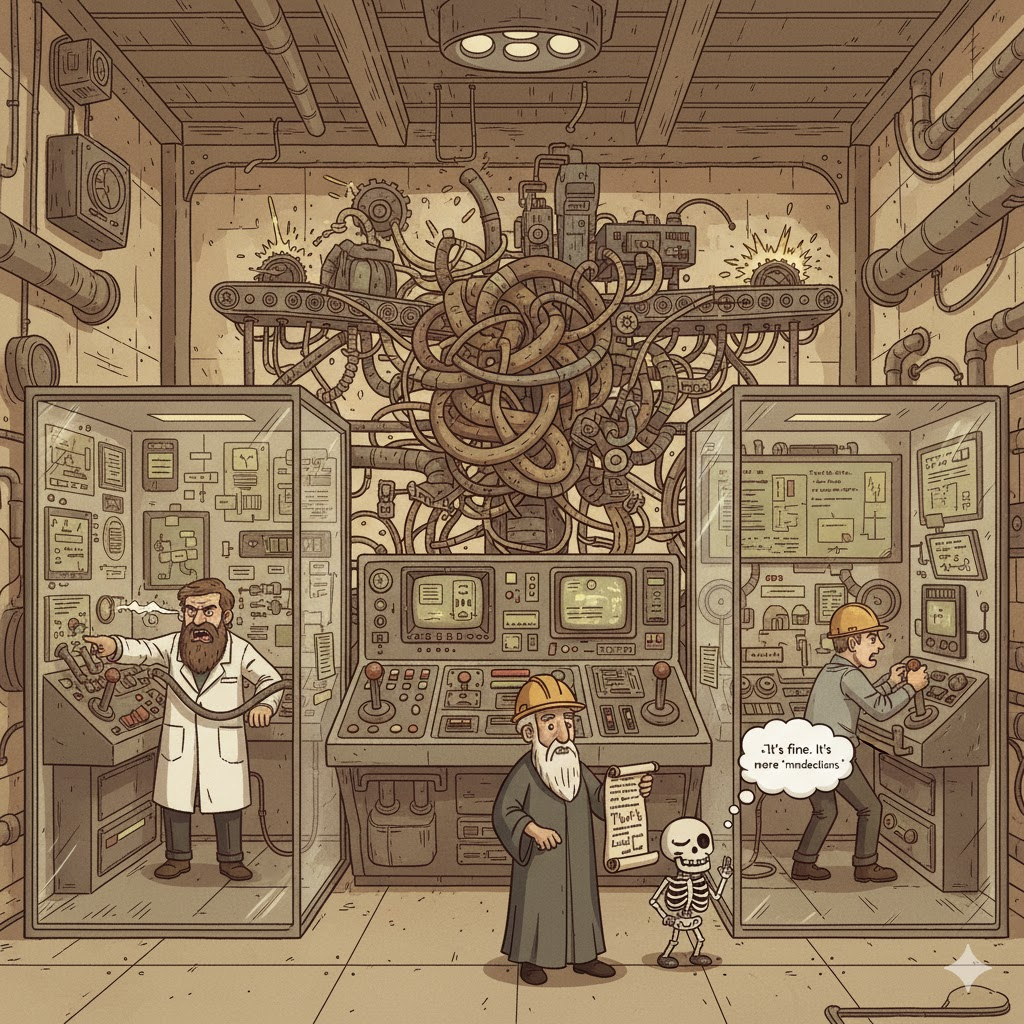

6. Conway's Law: A system's design will mirror the communication structure of the organization that built it.

- Profound Truth: Software development is a socio-technical activity. A system's architecture is not determined by purely technical requirements but is constrained and shaped by the human teams that build it.

- Implication: To achieve a desired architecture, you may first need to change the structure of your teams. This is known as the "Inverse Conway Maneuver."

- Failure Example: Apple's "Copland" OS Project. In the mid-90s, Apple's chaotic internal structure of competing teams was directly reflected in their attempt to build the Copland OS. The resulting architecture was a chaotic mess of conflicting ideas that never cohered. The project failed, forcing Apple to acquire NeXT to get the foundation for Mac OS X.

- Mitigation Example: Netflix's Microservices Transition. Netflix understood that to achieve a resilient, scalable microservices architecture, it had to change its organization first. They pioneered the "Inverse Conway Maneuver" by creating small, autonomous teams that had full ownership of specific services, thus ensuring their organizational structure would produce the desired software architecture.

- A Story from the Trenches: I was at a big company when it acquired a smaller rival. For the next year, I watched the engineers try to integrate the two platforms. The resulting architecture was a Frankenstein's monster. It wasn't designed based on technical merit; it was designed based on which VP won which political battle. The system's central data bus had three different competing formats because the three teams responsible refused to cede control. The code was a perfect map of the company's org chart dysfunction.

Category 3: On Implementation & Process

These rules apply to the act of writing and refining code. They guide a developer's priorities and day-to-day decision-making.

7. Knuth's Dictum (Premature Optimization): "Premature optimization is the root of all evil."

- Profound Truth: A developer's intuition about where a program spends its time is often wrong. Vast amounts of effort are wasted optimizing code that is not a performance bottleneck, often sacrificing clarity for a negligible gain.

- Implication: Write clear, simple, and correct code first. Use profiling tools to identify actual bottlenecks, and only then focus optimization efforts on those specific, measured hotspots.

- Failure Example: The PlayStation 3 Cell Processor. This processor was incredibly powerful but notoriously difficult to program for, requiring complex, manual optimizations from the start. This forced premature optimization led to many third-party games being buggy or performing poorly compared to their simpler-to-program Xbox 360 counterparts, hurting the console's early success.

- Mitigation Example: The Go Programming Language (Golang). Google designed Go for simplicity and clarity. Crucially, they integrated powerful, easy-to-use profiling tools (

pprof) directly into the standard toolchain. This design encourages a culture of "measure first, then optimize," directly embodying Knuth's wisdom. - A Story from the Trenches: I remember a brilliant junior engineer on my team who was obsessed with performance. He spent three weeks rewriting a data parsing function in C++ with bit-twiddling hacks to make it 50% faster. We were all very impressed. Then we ran a profiler. The function took 0.1% of the total request time. The other 99.9% was a single, slow database query. He had spent a month making the entire system 0.05% faster while making the code unreadable. I made him revert the whole thing. To make it a teaching moment, I printed a special t-shirt with the slogan "I optimized 0.05% of the system!" for him. He was a good sport and loved wearing that t-shirt to work.

8. The Law of Leaky Abstractions: All non-trivial abstractions, to some degree, are leaky.

- Profound Truth: Abstraction is our primary tool for fighting complexity, but it is never perfect. Inevitably, you will need to understand the details of the layer beneath you to solve a performance problem, debug an error, or handle an edge case.

- Implication: While we must use abstractions to be productive, we cannot be ignorant of the underlying systems. An effective engineer has knowledge "down the stack" because the details will eventually matter.

- Failure Example: The 2021 Fastly Outage. A single customer's valid configuration update triggered a latent bug in Fastly's underlying infrastructure, causing a global outage. The abstraction of the "customer configuration" leaked, interacting with the system in a catastrophic way that developers of the customer-facing API could not have predicted without deep system knowledge.

- Mitigation Example: Google's Site Reliability Engineering (SRE). The entire SRE discipline was created to manage this law. SREs are software engineers who are also experts in the underlying infrastructure. Their role is to own the full stack, understand where abstractions are likely to leak, and build automation to manage the resulting failures.

- A Story from the Trenches: We experienced a production outage that brought our entire service fleet to a halt. For six hours, we thought our code was the problem. It turned out that the managed cloud load balancer we were using—a "simple" black box—had a silent, undocumented limit on connection reuse that we were hitting under peak load. We didn't solve the problem by looking at our code; we solved it by reading the Linux kernel source code for TCP keepalives. Never, ever fully trust an abstraction.

Category 4: On Quality & Correctness

These principles address the fundamental challenge of building reliable and bug-free software. They define the relationship between code, testing, and correctness.

9. Dijkstra's Dictum (Limits of Testing): "Testing can show the presence of bugs, but never their absence."

- Profound Truth: It is impossible to test every possible input and sequence of events in any non-trivial program. Testing gives you confidence for specific cases, but can never formally prove a program will work for all cases.

- Implication: Quality must be designed in, not just tested for. Practices like strong typing, simple design, and code reviews are essential to prevent bugs from being introduced in the first place.

- Failure Example: The "Heartbleed" Bug in OpenSSL. For years, this critical security software contained a tiny bug—a missing bounds check. Despite widespread use and testing, no test case ever triggered it. Its discovery proved that even massive amounts of testing had failed to show the absence of a catastrophic flaw.

- Mitigation Example: The SQLite Database. The creator of SQLite, a database used in virtually every phone and computer, is deeply aware of this law. In addition to a massive test suite, he uses formal methods, static analysis, and fuzz testing, acknowledging that traditional testing alone is insufficient to achieve the required level of correctness.

- A Story from the Trenches: I worked on a real-time bidding system where, once every few months, a single server would crash and reboot. It passed a massive suite of tests with 100% coverage. After weeks of debugging, we found a race condition between the network interrupt handler and the garbage collector. This issue only occurred if a specific packet arrived within a 20-nanosecond window during a particular phase of garbage collection. No test could ever have found that. It taught me humility, and that quality comes from design, not just testing.

10. Weinberg's Law: "If a program doesn't have to be correct, it can be made arbitrarily fast and small."

- Profound Truth: The most challenging part of software is not making the computer do something, but making it do the right thing under all possible conditions. Handling edge cases, errors, and ensuring data integrity is the bulk of the work.

- Implication: The pursuit of correctness is the central, non-negotiable goal. When in doubt, always favor the simple, provably correct solution over a clever but complex one.

- Failure Example: The Therac-25 Radiation Disasters (1985-1987). This machine delivered lethal radiation overdoses due to a software race condition. The designers removed hardware safety interlocks, placing absolute trust in the software's correctness. The failure to ensure this primary goal—safe operation—made its advanced features tragically irrelevant and stands as the ultimate lesson in prioritizing correctness above all else.

- Mitigation Example: Avionics Software (DO-178C Standard). The software that runs airplanes is developed under the extremely rigorous DO-178C standard. The process prioritizes correctness and safety above all else, requiring formal methods, exhaustive documentation, and multiple layers of redundancy. Development is slow and expensive, but it's a necessary trade-off for a system where correctness is a life-or-death requirement.

- A Story from the Trenches: At a startup, we were obsessed with having the fastest API in our industry. To hit our latency targets, one team decided to skip some validation steps on incoming data, assuming it would always be well-formed. It was faster, and they got bonuses. Then a client sent a single malformed payload. It triggered a bug that cascaded through the system and corrupted two days' worth of customer data. The company almost went under. Being fast is great, but being wrong is fatal.