CFD - Part 1

In a previous post, we discussed the Navier-Stokes equations, which govern the behavior of fluids.

What is CFD? A Broader Perspective

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is a branch of fluid mechanics that uses numerical analysis and algorithms to solve and simulate problems involving fluid flows. It lies at the intersection of physics, mathematics, and computer science. At its heart, CFD is about translating the laws of nature — encapsulated in partial differential equations (PDEs) — into something a computer can solve.

Historical Roots and Pioneers

- Leonhard Euler (1707–1783): Developed the Euler equations, the inviscid form of the governing equations of fluid motion.

- Claude-Louis Navier (1785–1836) and George Gabriel Stokes (1819–1903): Extended Euler’s equations by incorporating viscosity, giving us the Navier–Stokes equations we rely on today.

- John von Neumann (1903–1957): A pioneer in both computing and numerical methods, von Neumann was instrumental in the digitization of PDE solving, particularly during WWII with shock wave and detonation modeling.

- Stanley Osher and Alexandre Harten (1980s): Developed high-resolution schemes (e.g., ENO, WENO) that improved the accuracy of CFD in capturing shocks and turbulence.

- The CFD revolution (1960s–1990s): With the advent of high-speed computers, pioneers such as Patrick Roache (Computational Fluid Dynamics textbook) and others formalized the field into a distinct discipline.

Motivation for CFD

Why did CFD become such an important tool? Because experiments and analytical solutions both hit walls:

- Analytical solutions: Only feasible for very simplified problems (e.g., flow in a pipe, potential flow around a cylinder).

- Experiments (wind tunnels, water tanks): Expensive, time-consuming, and limited in scope.

- Computational approach: Offers a flexible, lower-cost, and repeatable way to test ideas, designs, and hypotheses. For example:

- Aerospace: simulate wing lift and drag before building prototypes.

- Automotive: optimize aerodynamics to reduce fuel consumption.

- Medicine: model blood flow in arteries for stent design.

- Meteorology: predict weather patterns and climate.

Main Challenges in CFD

Despite its power, CFD is not “press a button and get results.” Key challenges include:

- Mathematical Complexity: The Navier–Stokes equations are nonlinear and coupled. In fact, proving the existence and smoothness of solutions in 3D is one of the Clay Millennium Prize problems.

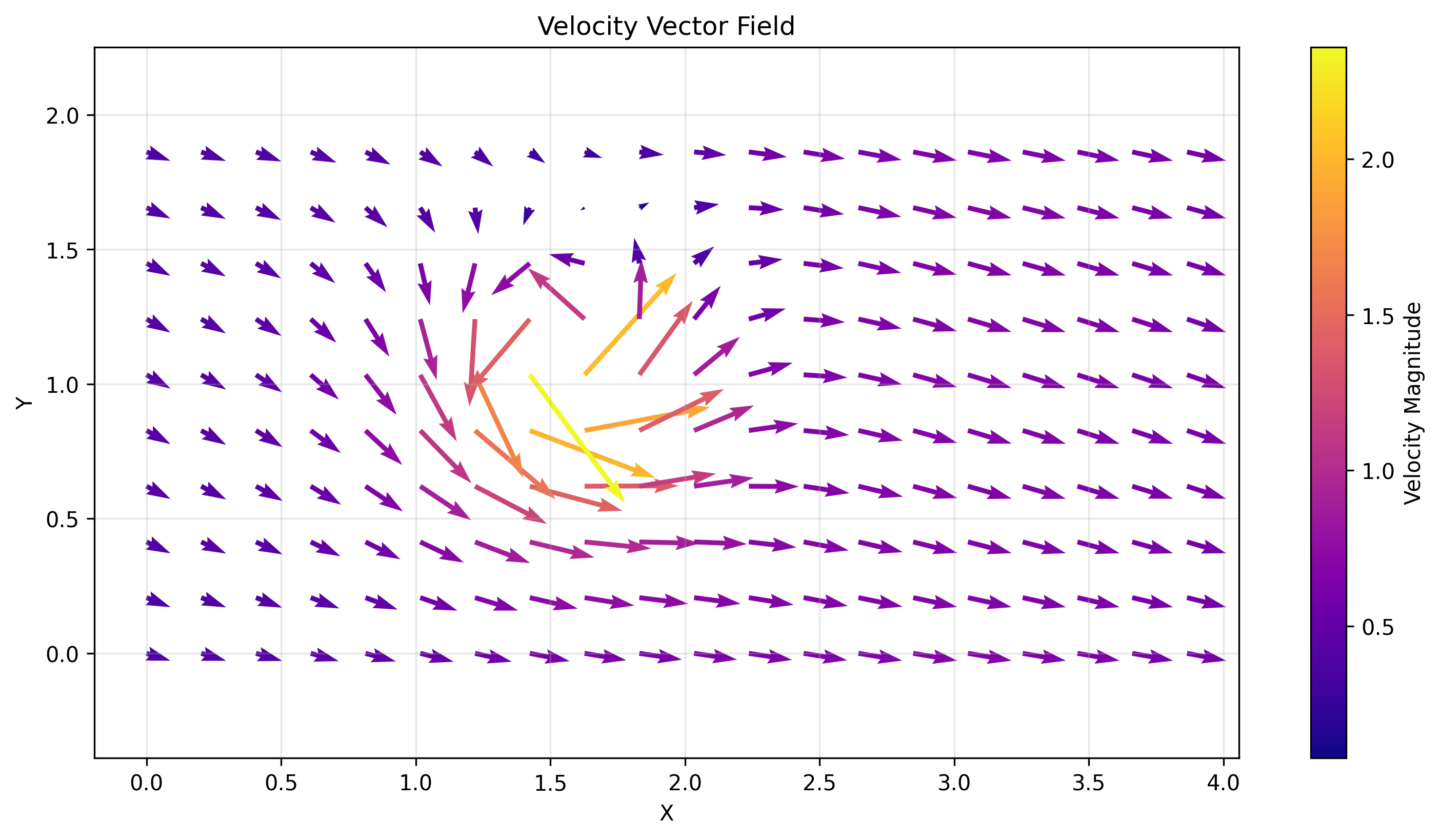

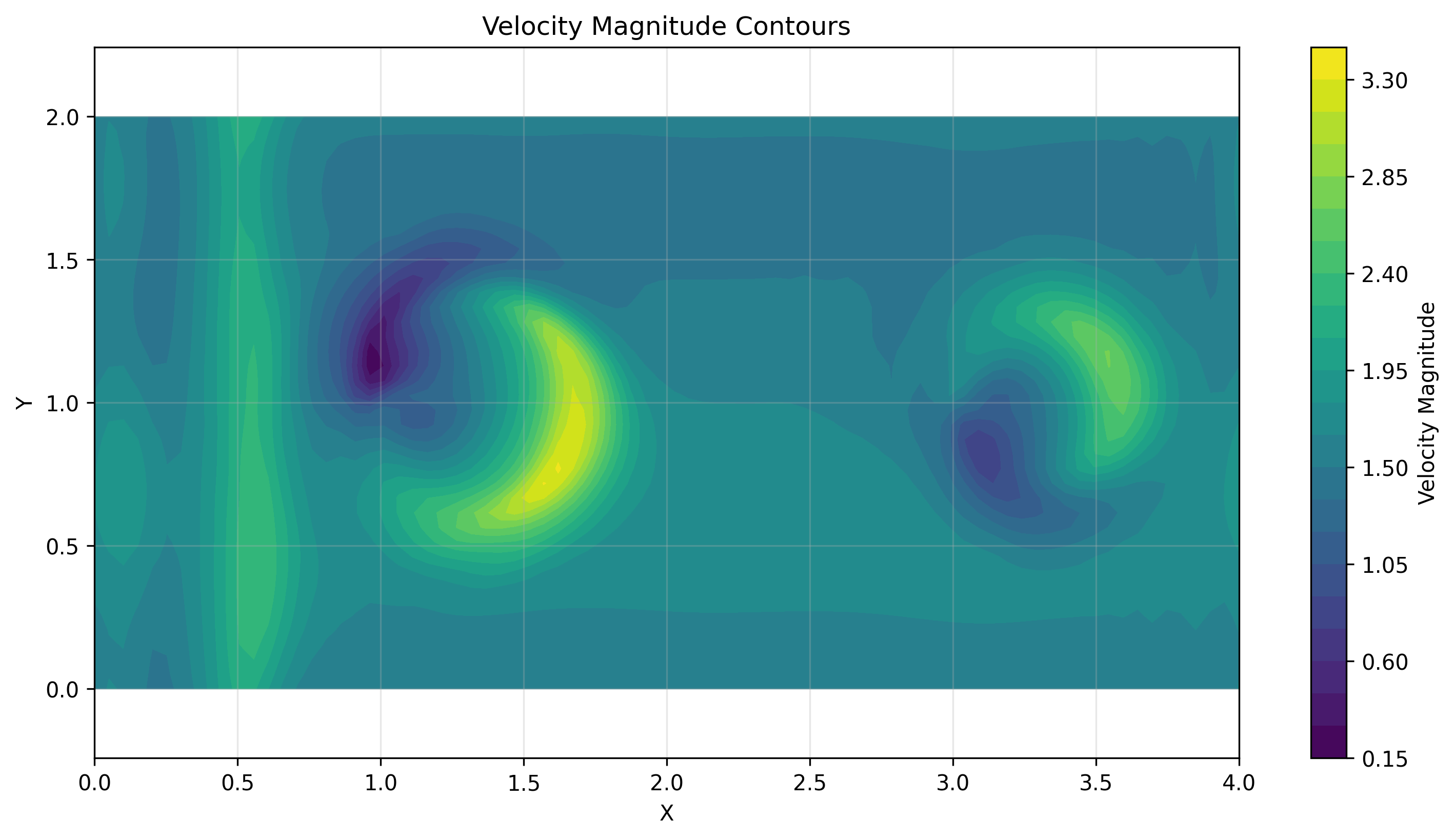

- Turbulence Modeling: Turbulence is a chaotic and multiscale phenomenon. Capturing it exactly requires Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS), which is computationally prohibitive. Engineers rely on turbulence models (RANS, LES) that trade accuracy for feasibility.

- Numerical Stability and Accuracy: Discretization introduces errors. Poor choices of grid resolution or time step can lead to instability (solutions blowing up) or inaccuracy (fake oscillations).

- Computational Cost: High-resolution 3D simulations involving millions of cells require supercomputers or HPC clusters, which often run for days or weeks.

- Validation and Verification: A CFD result is only as good as its modeling assumptions. Engineers must carefully compare simulations against experiments to ensure fidelity.

Where CFD Stands Today

Modern CFD is everywhere — from Formula 1 teams running overnight simulations, to weather agencies modeling climate decades ahead, to startups simulating microfluidics for lab-on-a-chip devices. Open-source and commercial solvers (e.g., OpenFOAM, ANSYS Fluent, COMSOL Multiphysics) have democratized access, while GPU acceleration and machine learning are pushing the next wave of breakthroughs.

Next

We embark on a journey to build a state-of-the-art CFD engine in C from the ground up. Stay tuned.

a chaotic and multiscale phenomenon